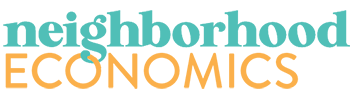

(Above: One of Thornton Dial’s pieces, “Don’t Matter How Raggly The Flag, It Still Got To Tie Us Together“)

Using the Lens of Culture to Craft Financial Tools

In Mr. Dial Has Something to Say we are told the story of an artist named Thornton Dial. Growing up poor in the Black Belt of Alabama, Thornton got his start not in art but in metalworking. He worked at a factory that manufactured trains for the better part of his life and during this time he maintained a steady art practice. By the the early 80s he had built up a significant personal collection.

Like many other African American artists in rural Alabama whose art making was a personal endeavor, his art would be largely hidden from the eyes of the public. It was only until 1987 when a man named Bill Arnett was introduced to Dial that this would change.

With the help of Arnett, Dial’s brilliant pieces, which explored a wide range of themes from history to politics, slowly trickled into galleries and collections. But the artist suffered from a strange problem of interpretation. Instead of labeling his work as simply ‘modern,’ the art community stamped Dial as narrowly belonging to an African American southern vernacular. As a result, his success suffered. Years later, after Dial’s work had been accepted into the Museum of Modern Art and other highly regarded museums, art historians would look at this past classification as a troubling act of mislabeling. They would come to see what is hopefully clear to readers of this post- that “outsider” implies being African American, self-taught, poor, or from rural Alabama disqualifies any artist from being seen as normal. They are not simply artists. They are “outsider” artists.

In a planning conversation a few days ago for a new project surrounding wealth creation in African American communities, Jessica Norwood pointed towards Dial’s story as a potent comparison to the work she is trying to do.

Jessica believes that the same type of false lens applied to Dial is being applied to how many see the world of financial tools and services for African Americans. To her, there exists a clear dominant narrative, an ubiquitous Picasso standard for what is preferred, for what is acceptable in the financial world. When this standard is placed in different cultural contexts like modern day African American communities, it fails to conform in any useful way. The “outsider” community is forced to conform to the Picasso-esque vision of normal, or else get shut out from the financial tools and services they need.

It was only after years of effort from patrons like Bill Arnett that allowed the art community to shift to accept Dial for the artistic genius he was. Dial never changed his style to conform to critics. The critics conformed to him. Jessica’s aspiration is to create a similar shift. Instead of making African Americans shift to accept financial tools and services designed for a different cultural majority, the tools must shift to conform to African American culture.

In order to fix this, we need to identify the cultural norms of African Americans that aren’t being addressed. Jessica identifies two:

For one, currently existing financial tools and projects are deprived of social reputation. There lacks an element of not only trust, but glamour. When the dominant financial narrative has been controlled by white voices for so long, being able to reintroduce trust into this space is essential. And to go the extra mile, to get users to not only trust but use a given service, we are going to be thinking about how to make it “sexy” too, as Jessica says. “You have to have a person or organization that has a social status or symbol attached to it.” Finding our own “Magic Johnson,” as she puts it, will be a unique challenge for this project.

Another important topic to address has to due with the consumer identity that has been placed on the shoulders of African Americans. Jessica believes that the psychological narrative of being the consumer has forced many African Americans to exist in a place of passiveness to larger corporations and institutions (financial service companies being a major culprit). She sees a strong source of potential in this mindset: “You have to be able to understand how they are marketed to in a consumption framework to be able to turn it on its head and get it into an ownership network.” Flipping this mindset is something that “we keep missing,” Jessica says, but something that this project will try to put a strong emphasis on.

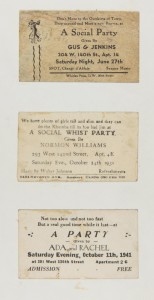

We’ve seen what it looks like when African American culture is the foundation of a financial solution. In the 40s and 50s in Harlem, renters who were low on rent money held Rent Parties. Although on the surface these parties were a medium for apartment owners to cover rent costs, they also served the purpose of strengthening the community and reinforcing cultural practices. In an environment of discriminatory pricing and lower wages for African Americans, these parties fostered a crucial sense of ownership.

In order to create new financial tools that capitalize on cultural ownership, we will also need to look at past solutions that haven’t been as successful as the Rent Parties. One example can be found in the South Carolina with credit unions that were successful for certain ethnic groups, but not for the African American community. According to Jessica, case studies like this one help with “understanding what those cultural push points and differences are that would make a system work.” In the failure of past projects lies critical feedback for this endeavor.

Diving deeper into what has and hasn’t worked is one of the major reasons Jessica is assembling her brain trust of experts. These surveyors will play a crucial role in understanding the landscape of African American culture and how this translates into appropriate financial tools.

In the next few posts on this blog, Kevin and Jessica will be sitting down with a handful of these experts who each will be speaking towards their experience implementing a specific financial service.

Check back soon for posts capturing these conversations.